|

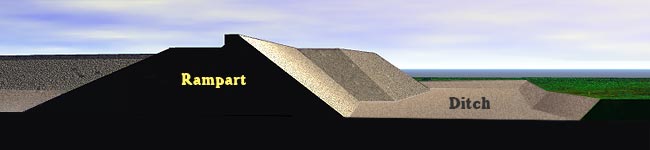

Rampart and Ditch |

Cannon drove fortification development. Cannon forced the defensive mind to adopt and refine in a very few years a type of fortification that was visually less impressive than stone vertical walls but far more resilient to the new force. The very first of these types of fortifications employed two fundamental elements:

- a rampart, sloped in front and low in profile, and wide enough at its top to permit men and cannon to be deployed there;

- a ditch (or moat) in front to hamper advancing attackers, any delay or even slowdown thereby exposing them to defensive fire.

|

| Compare the high curtain wall to the low, sloped rampart. Which is more likely to collapse? |

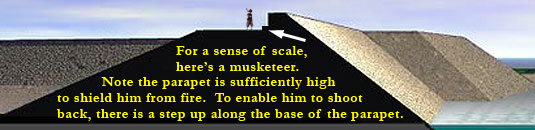

In cross section, unlike the stone curtain wall, the rampart was low and squat, wider than tall, with a sloped front. It did not defy gravity - it could not topple over. The first ones were made of earth with some reinforced with stone and wood. Cannonballs striking such a thick, earthen slope would merely bury themselves into it without breaking it down - gravity was no help. Keep in mind that in those days, cannonballs were solid, not packed with powder to detonate soon after impact. Their destructive power was in the punch. Being able to absorb them, low, sloped, thick walls became the fundamental strength of a new type of defensive design - but they had to be thick enough to withstand hits from a 24-pounder cannon.

The ramparts of an artillery fort were not as high as the walls of medieval times when the higher the wall, the better to fend off attackers with siege towers and ladders. For the artillery fort, artillery and small arms fire kept attackers sufficiently far from the ramparts. If defenders became so weakened and their firepower so depleted that attackers could reach the base of the ramparts, high walls would not stop them at that point.

The ditch in front of the rampart was conveniently created by shoveling out dirt to build the rampart. The ditch made the rampart higher from its base plus created a pit that slowed attackers and tended to entrap them. Thus, a secondary feature of the rampart defense became integral to its stopping any charge.

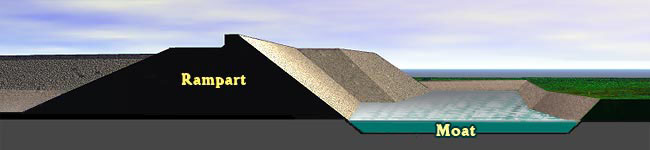

The Ditch Becomes A Moat

|

Nasty Enhancements to Moat & Ramparts |

Water in a ditch slowed attackers more than a ditch of dry ground (try running through water even only two feet deep with a mud bottom). A ditch could be filled with water if there was a convenient source like a stream or if the water table was high enough, which it usually was in some provinces of the Lowlands, such as Holland and Zeeland. Unfortunately for defenders of forts in northern locales like England, the Netherlands and the Baltic states, bitter weather in winter could put a coat of ice across the top of a moat sufficient to support attacking foot - and this period was well within the Little Ice Age.

A

rampart with a ditch/moat in front was not sufficient to stop an

assault. A third element was needed to cover these two with

shot. That third element of the trace or ground plan was so designed

that around a fortification's perimeter there would be no spot left

untouched by defensive fire - to make a play on words, no dead

ground so there would be only a killing ground.

A

rampart with a ditch/moat in front was not sufficient to stop an

assault. A third element was needed to cover these two with

shot. That third element of the trace or ground plan was so designed

that around a fortification's perimeter there would be no spot left

untouched by defensive fire - to make a play on words, no dead

ground so there would be only a killing ground.

The third element was the bastion.

| Back | The Bastion |

|

|

|