|

"For tis the sport to have the enginer Hoist with his owne petar" |

That quote is from Shakespeare's Hamlet, and even today the saying is used "Hoist with his own petard" to mean harmed by the same device or means intended to injure others. Indeed, in the period of our discussion, any attacker placing a petard risked self destruction should the fuse be too short or burn too fast - or if his escape was slowed because he was shot. Often, though, the petard setter never even had the chance to light the fuse because he was gunned down while approaching.

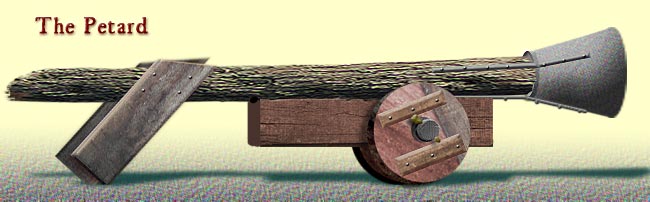

The petard above could be wheeled

into position. The petard below had a hook so that it could be hung from a spike

driven into the gate (from John Muller).

The petard was an explosive device brought up and set most usually on a gate or porticullis. It was either pressed to the gate or fixed to it with, say, a spike or two. Only a few men, perhaps even only one, were needed for the job. While there were many variants to the petard's appearance, the basic feature was an iron (or sometimes pottery) container shaped like a bell or a flower pot of today. It was packed with gunpowder and had a light cover on one end (simply to hold in the powder). That end was placed against the door. Some petards were light enough to be carried by one or two men (or in a wheelbarrow); others were mounted on a carriage to be rolled into place. Construction of that carriage could be quick and rough since it was going to be used only once.

Christopher Duffy, Fire and Stone, pg 95,

states that the wide part of the petard was NOT set against the surface but

instead opposite, so that upon detonation, the explosive force propelled the

metal (and any beam attached to its narrow end) in a rocket-like

fashion against the door to punch a

hole. On the very next page is a little illustration, from Malthus,

1629, showing the wide end of the petard set against the door, exactly

opposite what Duffy said. The petard illustrated in John Muller's work

strongly suggests the wide end was against the door. Plus, two images on

page 59 of John Tincey's Soldiers of the English Civil War (2)show

the wide part of the petard bell up against the gate. If any reader can point

to sources to support Duffy,

let me know.

The forces of the young Henry of Navarre (to be Henry IV of France) made first use of the petard in 1580 against three gates of Cahors. Although the blown holes were small, they were swiftly enlarged with axes and soldiers crawled in. The French became famous and in demand for their petard expertise. But by 1689, the Chevalier de Guignard mentioned that he had not seen or heard of the petard being used by that time. His contemporary Saint-Rémy explained: "... hardly any officers ever return from these uniquely hazardous expeditions; as soon as the garrison troops see what is going on, they open fire on the petardier from the gate and the flanking defences. They seldom miss."

Contemporaries of Shakespeare also spelled that word without the 'd,' in which case its resemblance to the French word "peter" for - ahem - "fart" is very possibly more than coincidental.